29 November 2022

The annual Wildlife Crime Report compiled by Wildlife and Countryside Link, with information from groups including RSPB, WWF UK, and the League Against Cruel Sports, has shown that crime against wildlife in 2021 was at record levels. [1] Wildlife crimes include, for example, hare coursing, persecution of birds of prey, badgers and bats, disturbance of seals and dolphins and illegal wildlife trade.

In England and Wales there were 1,414 reported wildlife crime incidents (outside of fisheries), almost exactly the same level as in 2020 (1,401). There were 3,337 fisheries crime reports in 2021, down from 4,163 in 2020. [2] The scale of wildlife crime is likely to be far higher than the report details, due to lack of official recording and monitoring of most of the data relying on direct reports from members of the public to nature groups. [3]

Dr Richard Benwell, CEO of Wildlife and Countryside Link, said: “Wildlife crime soared during the pandemic and remained at record levels this year. Progress on convictions is positive, and we welcome DEFRA’s efforts to stiffen sentencing, but overall that is of little use while the rate of successful prosecutions remains so low.

“The snapshot in our report is likely to be a significant under-estimate of all kinds of wildlife offences. To get to grips with these cruel crimes, the Home Office should make wildlife crime notifiable, to help target resources and action to deal with hotspots of criminality.

“The Retained EU Law Bill threatens to be a serious distraction, and could even lead to important wildlife laws being lost. Instead, seven years on from its publication, the Government should implement the Law Commission’s 2015 wildlife law report. Surely it is better to spend time and money improving laws that are as much as two centuries old, than wasting time reviewing effective environmental laws under the REUL bill.”

Martin Sims, Chair of Link’s Wildlife Crime Working Group, said: “We must empower police forces to act on wildlife crime. We already see how, with proper resources and training, a real difference can be made in the work against awful crimes like hare coursing. It’s the counties with well-funded and resourced projects in place where we’re seeing the most positive progress. Also essential to efforts to better protect our wildlife is making wildlife crime notifiable, and recorded in national statistics. This would better enable police forces to gauge the true extent of wildlife crime and to plan strategically to address it.”

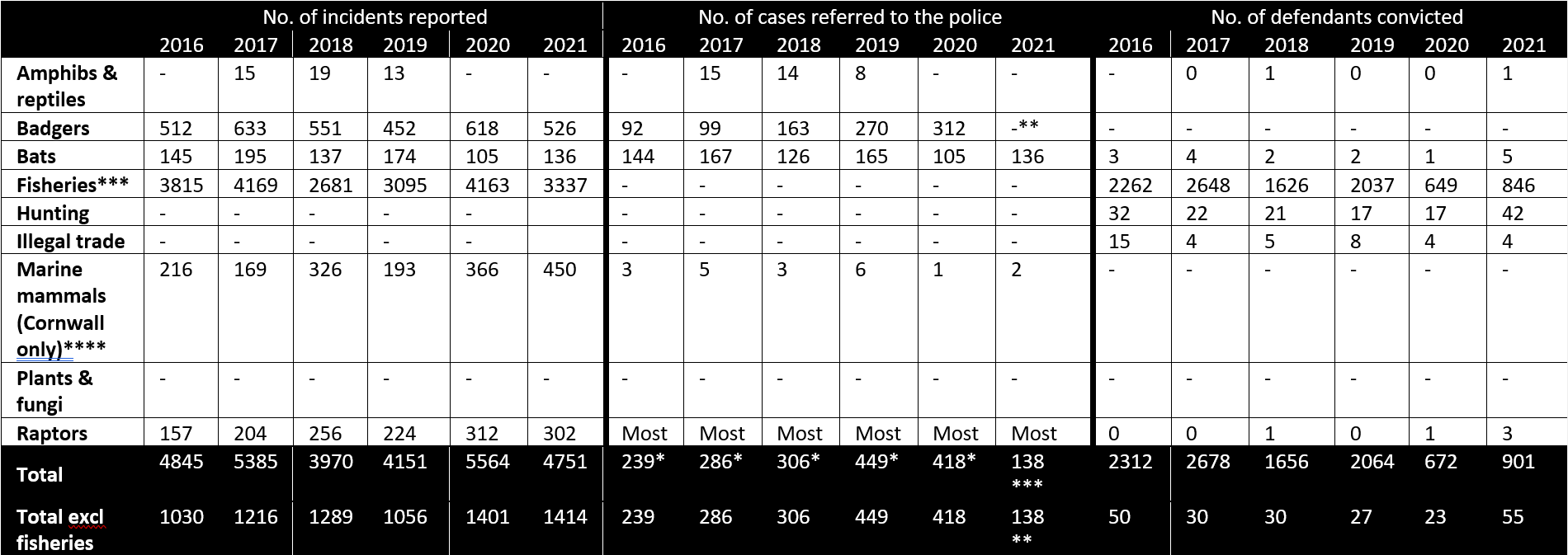

Table 1. Wildlife crime incident reporting, referrals to police and convictions

*Most raptor incidents are referred to the police, but exact numbers cannot be confirmed so are excluded from the total figures.

** Please note the lack of data for badger crime referrals to the police in 2021 explains the large fall in the overall from the 2020 total figure

***Fishing crime figures for 2020 and 2021 are for England and Wales, prior to this they are for England only

**** Marine figures are for Cornwall only due to lack of recording nationwide, with these acting as an indicator of national trends

The pandemic contributed to the high wildlife crime reporting figures in both 2020 and 2021. COVID-19 restrictions appear to have increased reporting of wildlife crimes in several ways. Opportunistic offenders may have felt that with the police busy enforcing social restrictions that wildlife could be harmed with relative impunity. With increased use of the countryside and coast in the pandemic more members of the public were also present to witness and report incidents of concern. Increased domestic tourism also played a role in increased wildlife disturbance of marine mammals.

There was a positive increase in convictions in some types of wildlife crime in 2021. [4] But low levels of prosecutions and low conviction rates are an on-going challenge in tackling wildlife crime. Despite the number of convictions in 2021 being more than double the rate in 2020, there were still only 55 convictions for wildlife crimes in the whole year (if well-resourced and enforced fisheries crimes are excluded - see note 2 for more detail). And for hunting crimes alone more than half (53%) of prosecutions were unsuccessful in securing a conviction in 2021. This is compared to an 82% conviction rate across all crime. A lack of training and resources is central to this issue.

The report highlights the difference in what can be achieved with the right budget, training, and resources, with concerted action to tackle hare-coursing being a main factor in the increase in convictions in 2021. This follows a nationwide police operation to tackle the issue - Operation Galileo – achieving good results. Consequently 2021 saw the highest number of cases proceeded against accused hunting crimes since 2015, with 80 cases taken to court. The highest increases in prosecutions were in Norfolk and Suffolk where police forces were active in Operation Galileo and other police activities designed to reduce the impact of hare coursing. This policing focus corresponded with legislative action, which has seen hare coursing sanctions increased in the Policing, Crime Sentencing and Courts Act 2022 (rising to up to 6 months imprisonment and unlimited fines). Similar action needs now to be taken to enable the more effective prosecution of other hunting crimes, including the illegal hunting of foxes with dogs.

Despite this positive legislative move, one new Bill from Government could actively worsen wildlife crime. The Retained EU Law Bill is intended to ‘save, repeal, replace, restate or assimilate’ the retained EU law (known as REUL) applying in the UK within a set time period. These laws include the Conservation of Habitats and Species Regulations 2017, which make it a criminal offence to damage the habitats of key species including badgers and bats. Such habitat offences form the majority of the wildlife crimes against badgers and bats. The Bill is likely to lead to the hasty rewriting of the regulations, potentially weakening the legislative underpinning for tackling common wildlife crimes.

To properly tackle the issue of wildlife crime, nature experts are calling for the following actions (most of which were also recommended by a UN report in 2021):

Latest Press Releases